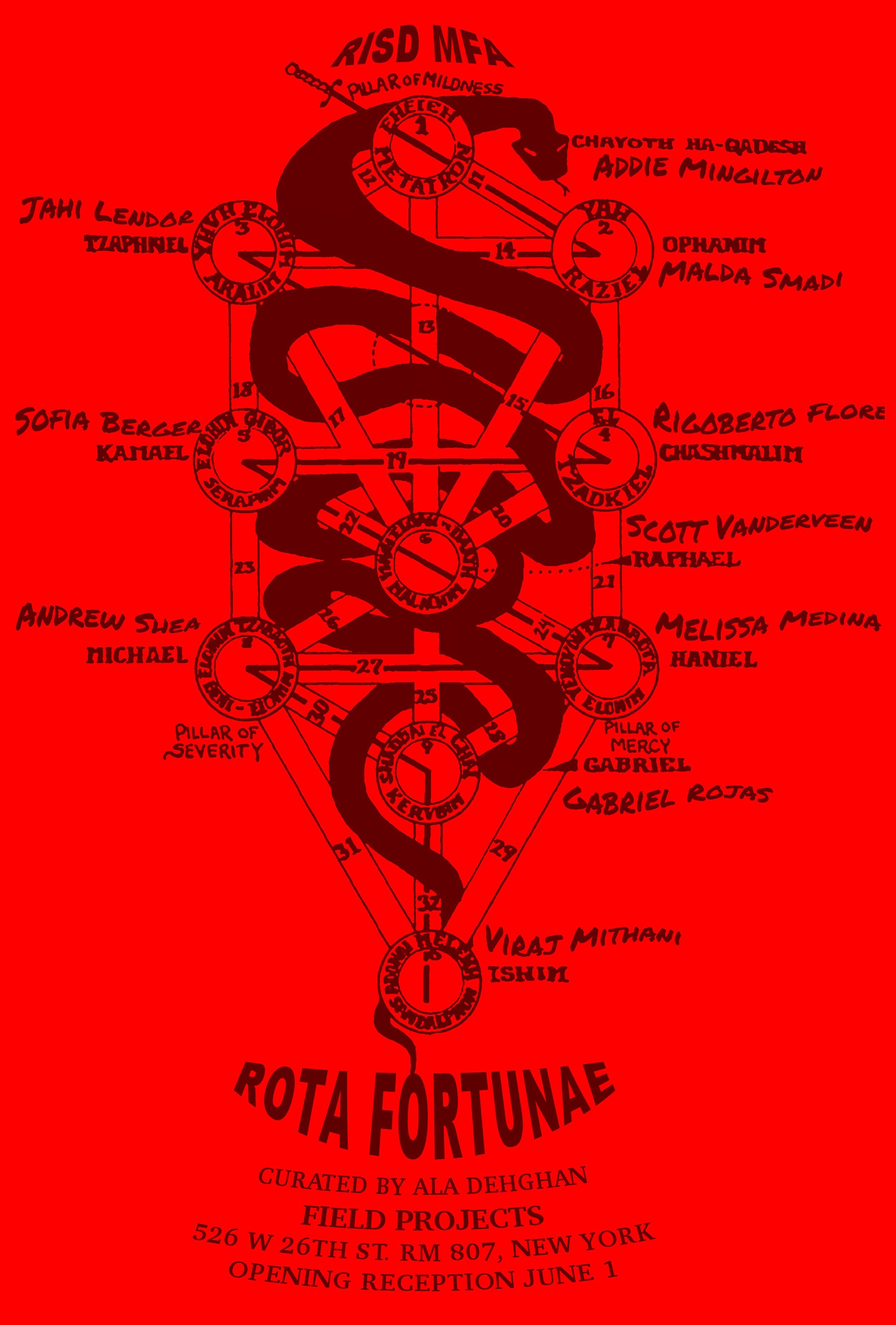

ROTA FORTUNAE

RISD MFA SHOWCASE

May 30th-–June 24th

Curated by Ala Dehghan

Addie Mingilton Andrew Shea

Gabriel Rojas Jahi Lendor

Malda Smadi Melissa Medina

Rigoberto Flores Scott Vanderveen

Sofia Berger Viraj Mithani

In the Tree of Life, the Wheel is placed on the Pillar of Mercy, where it forms the principal column linking Netzach to Chesed, Victory to Mercy. It is the revolution of experience and progress, the steps of the Zodiac, the revolving staircase, held in place by the counter-changing influence of Light and Darkness, Time and Eternity - presided over by the Plutonian cynocephalus below, and the Sphinx of Egypt above, the eternal Riddle which can only be solved when we attain liberation. The basic colors of this Trump are blue, violet, deep purple, and blue irradiated by yellow. But the zodiacal spokes of the wheel should be in the colors of the spectrum, while the Ape is in those of Malkuth, and the Sphinx in the primary colors and black.

Sofia Berger, Turn Right, Oil on canvas, 36 X 48 inches, 2022

Sofia Berger

When I was four years old, my uncle sat me in his bike basket and rode with me through our neighborhood. He quizzed me incessantly, until I could finally distinguish left from right. It was a formative lesson in mapping my surroundings, and it allowed me to better orient myself within my own world. I was born in Požarevac, a small town located in Serbia. My parents and I moved to Canada when I was five. Asking questions surrounding migration has emboldened me to pull from reality to mentally render new environments. Painting grants me permission to continuously reach for destinations, allowing an emotional transition from one reality to the next. It requires me to slow down and to consider those people and entities that have informed my personal geographies; to consider all the variables at hand that have shaped how I view the world at the present moment. Not knowing what’s going to happen next, or where I’m going, is integral to my overall painting process. But my invention, repetition and movement of spaces relies, paradoxically, on certain restrictions. In order to enter spaces that I’m creating, I need something to hang the gestures onto. I’m building my own visual lexicon rooted in the tangible; taking existing forms and making them fictitious. A ladder, for instance, is a symbol of human engineering. It has verticals and horizontals; the lines are straight. But in my paintings, the ladder’s function is less obvious. Rather than a simple, straightforward tool that facilitates upwards or downwards movement, it becomes a scaffolding device that holds pockets of spaces within and around it. These pockets have offered the freedom to explore a more ecstatic coloristic experience.

Malda Smadi

When a dislocation of any type occurs, whether geographical, emotional, or spiritual, the disorder pushes the self to retreat to safety. For me, that safety is in my body. It is in this place of retreat where I locate my original home. In this space of translocation, I forage for materials from my surroundings and places that I belong to. Moving between Dubai, Damascus, Beirut, and Providence, I shape a reality dependent on what is available. I then transform these materials, searching for the forms and relationships that emerge while meditating on home and the body as a moving vessel and container for attachments. My work involves various modes of reflection through making. Drawings help with understanding experiences, while material and form are the physical structures that embody personal narratives, histories, and realities of non-belonging. I am interested in transitions and transformations as they occur, whether in the self or in the work. I am drawn to beauty as a form of hope, rather than the pervasive violence and pain that follows the bodies of people from the Levant diaspora. Hope exists in the new generation that escaped the holds of the greatest burden, carrying the legacy and memory of our parents and ancestors through time and place. Two questions emerge: How do we locate ourselves? How is memory of the homeland imprinted on the body?

Scott Vanderveen

Scott Vanderveen, Green Wood, wood, plaster, foam, paper, wax, oil paint, 48 x 25 inches, 2023

A memory palace is a mnemonic device that facilitates recollection by putting memory, that slippery substance, into a strictly structured mental geography. It is advisable to use a real place with which you are intimately familiar (perhaps your childhood home) as the scaffolding for the compartmentalization of whatever mental objects require organizing. Other objects, sensations, or atmospheric conditions are used to heighten the efficacy of the system—memory #1 may be found in the junk drawer in the kitchen, at dusk, nestled between a box of safety pins and a bundle of rubber bands. I am interested in the way this mnemonic system imbues mind with matter and vice versa. With each object that I make, I hope to further collapse such divides, whether between subject and object, painting and sculpture, or play and whatever the opposite of play is (hard to say). My work, like the memory palace, investigates the ways in which material is transmitted, utilized, and preserved. Memory, on a personal as well as a cultural scale, seeps from the apertures of my objects or clings to their surfaces like residue. The histories we are born into, the identities we embrace or reject, our desires and our ways of being are betrayed by the objects that we surround ourselves with. These abstractions become especially legible in the ways we categorize, organize, and tend to said objects. In my studio, the uncanny is grafted onto the banal, and the natural is wed to the artificial. I work to upend and re-orient the normative structures that unfold as the material manifestation of ideology, perverting the rules of these structures and searching for ways to make sense of their violence, contradiction, and absurdity.

Gabriel Rojas, Composition with Red, Blue, and Yellow- Rumi Maki, wood, oil, canvas, fabric, rope, yarn, found objects, 93.5 x 62.5 inches, 2022

Gabriel Rojas

Inherited Abstraction: Painting for me is the arena where process connects with ritual and memory. Drawing from languages of Western modernist abstract painting and Andean textile design, I explore how the manipulation of painting, textiles, and traditional techniques can create tensions to reveal ideas about ancestral inheritance and transference, familial upbringing and psychological contradiction. Through investigating legacies of making, I invent studio rituals using formal painting moves and quotidian references to arrive at a place of intimacy. Alongside painting, different materials like rope, textiles and wooden constructions engage this process in which each physical act prompts new ways of revealing and reveling in the in-between stages of memory. My work is open to a fluid process of revision, re-order and re-use. The provisionality of my abstract painting is a way to expand from established structures, languages, and modes of making; to overcome its boundaries and reveal its new potential.

Despedida (Triptico)

Melissa Medina, Despedida (tríptico), óleo sobre panel, 2021. 8 x 10 inches; 9 x 12 inches; 8 x 10 inches (25 x 32 inches total), 2021

Melissa Medina

My grandfather Ramon Juarez passed away on March 23, 2015, almost 3 months to the date from when his wife, my grandmother, Ramona passed. This wasn’t my first encounter with death, that happened when my other grandfather Jose Medina Gonzalez passed on December 2, 2006. I was 14 then, it happened pretty quickly, one moment he was here visiting the family, the next he was diagnosed with cancer, and in a couple of months he was gone. It was fast, it was sudden, and honestly I was too young to understand what had just happened. But this death, the death of my maternal grandfather was different. We were still grieving my grandmother, but he was already in a hospice facility and it felt like there was no room to breathe before he too passed. It was hard for him, I realize that now, his wife - who he had married when he was 17 and she was 14 - was gone, his children no longer got along, his masculinity was constantly challenged as he depended on his daughters more and more…he was tired. The time after his death was different from anything I had experienced - it was a first for many things: the first time encountering death so closely, the first time confronting my own mortality, the first time I turned to nostalgia for comfort, the first time I realized that there is a limbo that lingers immediately after a person's death that is fueled by nostalgia, the first time I understood that even in death there were still ways in which we would feel othered. When immigrants are pushed into marginality they will, at times, turn to nostalgia for comfort, for security and for reassurance. While my family mourned here in America we imagined what it would be like to mourn in Mexico, in our rancho, with our community, with his community. We wondered if the grieving would be easier if he hadn’t been taken from us and placed into a cold refrigerated box while we grieved at home, separated. We struggled to leave him at the end of each day, when the funeral home would kick us out because they wanted to go home but we didn’t, because he was there and we weren’t. We knew that back home we wouldn’t be questioned, we wouldn’t be separated, we could take our time.

Addie Mingilton, GRIS GRIS, Creole Magik, Ritual. 64 x 36 inches, 2023

Addie Mingilton

My approach to painting during my time at RISD has changed not only through its procedural methods but its material methods as well. This is due to my own realization of where the work is being made and who is viewing the work during and after receiving an MFA. I am here to receive a $40,000 piece of paper representing the commodification of the artist and their works privy to the caste system within the art sphere. However despite the many studio visits telling me otherwise I will not become a piece of the system that burns my skin when touched. They want me to be grateful that they let me be here, and among them. Instead I will surround myself with love, my higher power. I am here for my ancestors that were brought in chains, I am here for those that never made it out and will never make it out. I realize that my existence within the higher education system is literally taking years off of my life. All so that I am ready to face the “real world” afterwards. But through this I have learned that I must hold my ancestors and their love by my heart, they make me and I make them.

Andrew Shea

I have been making paintings constructed loosely from my experience of walking one mile each morning from my apartment in Fox Point to Fletcher Building in downtown Providence, and of walking back each night. My goal is to rediscover the feeling of these close-at-hand places—their lights, atmospheres, colors, and topographies—through the process of painting in the studio. As such, these visual representations are not straight-forward and objective, but oblique and affective. The paintings often incorporate people, who are also ideated. I think of these figures and faces, in part, as metaphors for painting itself. When we look at paintings, we “face” them. In some way they mirror our own faces and look back at us. My figures often look at one another and hail one another. Sometimes they seem to think or speak silently, using not words but a kind of abstract paint-language of colored marks. In staging these exchanges and thought processes along the painted surface, I think I am asking: is real contact possible, whether through language or through painting?

Jahi Lendor, SECONDS TILL FREE AS THE SPIRITS OF THOSE WHO LEFT US, BE, Cardboard, dyed paper towels and bags, sugar hardenings, shopping cart basket, fake gucci bag, reusable shopping bag, plastic bags, foam, tar black spray paint, iron wind chime. 51 x 34.5 inches, 2023.

Jahi Lendor

A comedian said, “American pie isn’t made out of apples, it’s made out of whatever you can get your fucking hands on.”1 With that, my work seeks to provide an honest representation of the infinite value of the everydayness and behavior of blackness ranging from trauma to beauty. Various mediums explore culture, class, collective memory, identity, and erasure. While resisting institutional and systemic boundaries between disciplines my practice actively seeks fluidity between media. The work often translates to (social) poetic-bricolage visualizations that combine gestures of assemblage, sculpture, installation, and painting. The work focuses on reflecting on how I see life and my environment, which translates to a multi-melaninated reality of the Black experience. I’m learning and pulling from history and retelling and making a new history from the present within the present. Like the wildstyle subway graffiti artists, I’m stating “I WAS HERE”.

Viraj Mithani

My studio work and my personal experiences are inextricably intertwined and sometimes contradictory. Spiritual and violent, natural and plastic, attached and detached—they all coexist in me. You can’t search a soul by dissecting a heart, but only by connecting with it. This thesis is organized in three parts, which correspond to the three learning structures that inform my painting—inherited/experiential learning, academic learning, and tangential learning. I describe all three in a collection of narratives, reflections on cultural phenomena, and interpretations that seek to reclaim marginalized histories. I want to shine a light on the intersectionality between academic art, global art histories, intergenerational artists, and arts professionals. I find a lot of inspiration in activities that are pursued outside the studio that contribute to my process while making work. The art of bridling and handling reins to create drawings with lyrical lines. There are constant parallels to be found. I have incorporated findings from peers, critics, visiting artists, and faculty, chronicling their critical response to my work.

Rigoberto Flores, PURO PICHE PEDO (A LA VERGA), Streamer cardboard paint thread on muslin, 10 feet x 9 inches, 2023.

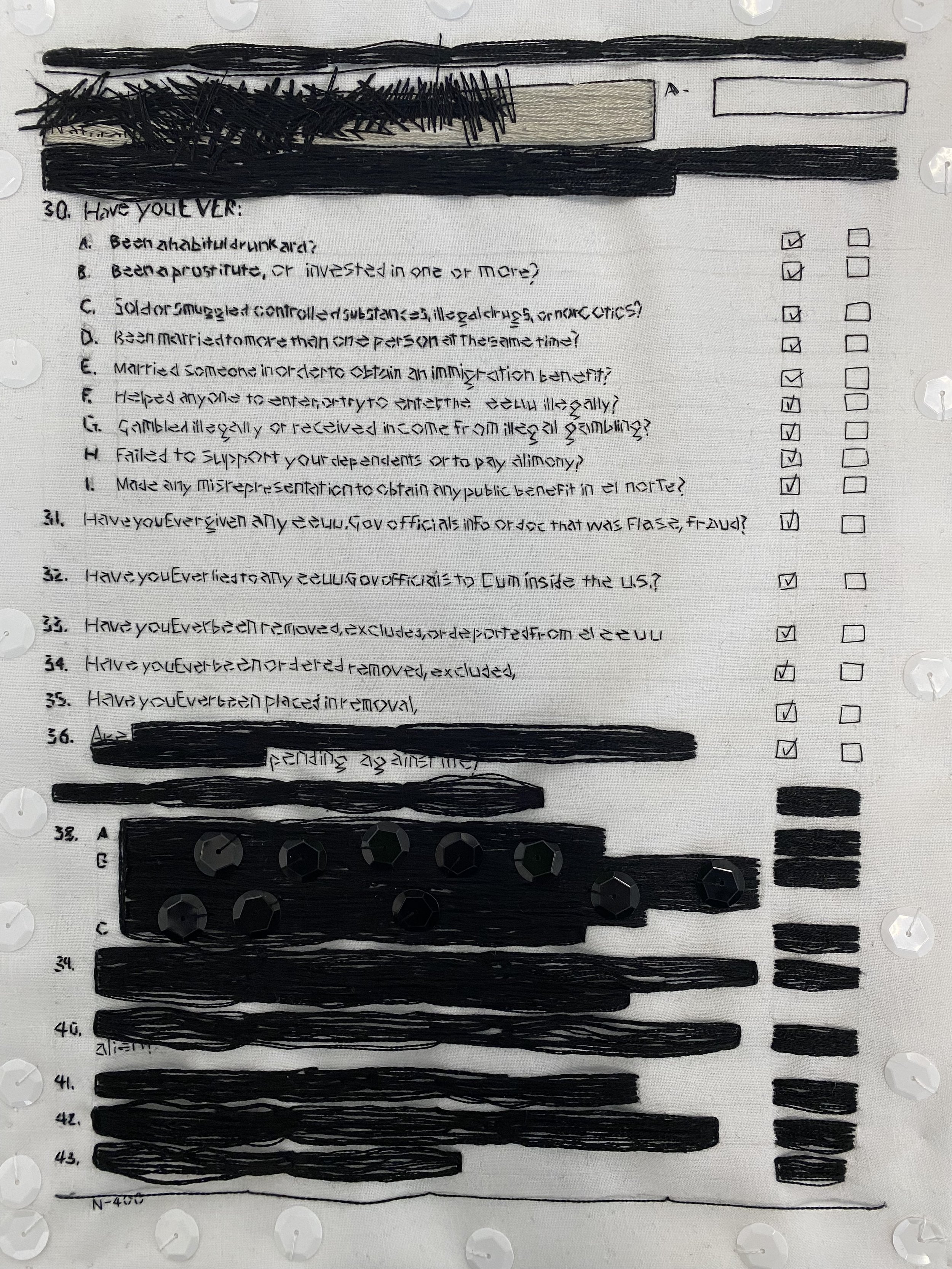

Rigoberto Flores

My name is Rigoberto Flores and I was born in Guerrero, Mexico. The work I make involves politics, immigration, cartel violence and religious themes. I’m interested in presenting these challenging and difficult concepts, to have them remain in the public consciousness. The work I produce involves charcoal drawings, textiles, print, and painting. The work I create is intended to address inconsistencies in established ideas, usually involving government violence. Throughout history art has been used to promote institutional propaganda. I am searching to do the same, but to oppose those structures. In recent work I’ve been creating images on tortilla warmers to emphasize my cultural background. Cartel violence in Mexico is prevalent in some areas, including the state where I was born. Farmlands are being taken over by cartels to grow illicit drugs. The images embroidered over the tortilla warmers are a sort of violence imposed on the cultural significance of the objects. The religious images depict how it was also used to violently colonize the country of Mexico.